She is one of the last of the dolce vitas, an artist still working high in the rosemary-scented hills of central Italy. Gone are the Ray-Bans and Vespas, the Venetian masked balls with Gore Vidal , the Roman dinners with Fellini , Grace Kelly , Liz and Dick. Years have passed, and people too. But at 90 years old, Beverly Pepper —who over the last 40 years has left an indelible stamp on this idyllic town, while the serene Umbrian landscape left its mark on her work—is still creating monumental art.

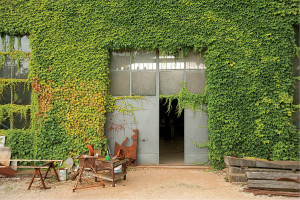

Seventy miles from Rome, five miles of dirt road outside Todi, a steep driveway lined with cypress culminates in a spectacular view of the surrounding landscape, a wash of sky and clouds above a rolling horizon. Here, one finds Pepper’s ivy-covered studio and sprawling terra-pink house. A swimming pool laps at the horizon beside a geometric Pepper-designed landscape—a slant of ball-shaped bushes and cypresses trimmed into perfect rectangles, planted in a circle around a stone patio. The front door sits in the shadow of one of Pepper’s massive sculptures, a 10-foot-high curve of rust-colored steel with a narrow slit in the middle framing the distant dome of the church of Santa Maria della Consolazione, rumored to have been designed by Leonardo da Vinci’s associate Bramante.

It’s lunchtime, and a cook has prepared spaghetti with lemon cream and a salad of greens pulled from the kitchen garden. Around the table, Pepper, her 96-year-old husband, writer Bill Pepper , and two art studio assistants crack open a bottle of cold local white.

Living in Rome in the 1950s, Bill and Beverly first brought their convivial American style to postwar Italy at a time when, Beverly recalls, “everything seemed possible.” As Newsweek’s Rome bureau chief, Bill hobnobbed with prime ministers around the Mediterranean, invited the starlets he was profiling over for meals and amused everyone at long lunches and dinners with his scandalous Vatican gossip. Beverly, with her Julie Christie lips and Irish setter–red hair, made sculptures out of iron and sailed to the top of the international art scene when she was 40, becoming the only female artist at a major gallery in Rome, Marlborough, an international operation that also represented Robert Motherwell. Unlike that late master of Abstract Expressionism, Pepper is still hard at work, putting together her seventh solo U.S. show for Marlborough, in New York, next year. And she just won the 2013 Lifetime Achievement Award from the International Sculpture Center, for which she will be feted at a gala in Manhattan this month.

Pepper is often compared with two women who continued to produce art at advanced ages: Louise Bourgeois and Louise Nevelson. She admires both, but vehemently rejects the “sculptress” label. Her medium, steel and iron, and many of her works—tools and pillars she calls sentinels—could be called masculine, but she rejects that label, too. “I use metal like paper,” she says.

At lunch, Pepper and her two assistants are discussing how best to ship her latest piece, a four-ton curve, to the buyer—a German count who wants it for one of his castle lawns. The conversation shifts to how Pepper acquired her own former castle, Torre Olivola, the one with the tower visible from her front door, which the couple bought in 1972 and owned for nearly 30 years before moving a few hundred yards down-hill to a wide one-story house that Beverly designed. “The castle was a ruin. I saw it, and I said to Bill, ‘You have to get that for me.’ ” They attended an auction and came in with the high bid by just 272 lire. That piece of good luck reminds Beverly of how their late friend Martha Gellhorn (war correspondent and Ernest Hemingway’s third wife) used to say that life is filled with “signposts of luck” that one must recognize.

Beverly Stoll , born in Brooklyn in 1922, always recognized those signposts. She grew up in a middle-class Jewish household where the art on the wall consisted of “a beautiful, tall ship painted on velvet.” Her father sold carpets and fur coats. She helped pay her way through Pratt by doing hand-painted lettering for advertising companies, launching a career in the field well before the Mad Men era. After the war, she gave up commercial art entirely and moved to Paris in 1949, studying with Fernand Léger and André Lhote at the Académie de la Grand Chaumiére.

“I didn’t think I wanted to sculpt. I wanted to paint,” she says of her early years. But in the early 1960s, living in a house with a garden that contained 33 felled chestnut trees in Rome, she felt inspired to begin sculpting wood. She moved from wood to metal after a curator asked if she could weld pieces for the groundbreaking 1962 exhibition “Sculture nella città,” in Spoleto. She didn’t know how to weld, but gamely fibbed. “I figured I could learn between then and spring,” she says. She became the only woman among 10 sculptors in the project, which involved steel factories across Italy, with other artists such as Alexander Calder , David Smith and Arnaldo Pomodoro.

A serendipitous series of events—a Rome show, a Time magazine review and Spoleto—put her on the art world map. During the ’60s, experimenting in the steel factories of Italy, she perfected her work, first creating polished stainless-steel boxes that reflected the landscape. She then began working with Cor-Ten steel, an especially weather-resistant industrial alloy, making huge sculptures that resembled ancient tools. In the ’70s, she moved on to large-scale earthworks, creating her first “amphisculpture” in 1974. She showed regularly in Rome and New York and began receiving commissions for public art from Japan to New Hampshire. In 1980, she put in half a year at the John Deere factory in Moline, Illinois. Working in cast iron with American metalworkers there, she produced monolithic sculptures inspired by screwdrivers and files.

“No woman in history has done what Beverly has done, which is to make the monumental outdoor pieces fabricated with factory techniques,” says the art critic Barbara Rose. “No woman has gone into a factory and worked right alongside the workers.”

In recent years, fabricating individual works at a factory, located in nearby Assisi, she has moved from pillar to curve. Her last New York show was called “Curvae in Curvae,” and works for the next show are elaborations on the same theme. The cavernous steel factory in Assisi, where she is producing work for her next show, contains a row of finished and half-finished colossal broken circles and spirals.

TODAY, PEPPER’S WORKS are installed in public and private spaces around the world, from Lithuania to Japan, Seattle to Venice. She has produced in-ground sculptures, mega-landscapes of rock or metal protruding from the earthlike modernist ruins. Her amphisculptures are artistic references to the outdoor theaters of ancient Greece and Rome. (The first and best-known of these sits inside the AT&T headquarters in New Jersey.) In Italy, besides the Todi pillars, a rusty curve slices the air outside St. Peter’s church in Assisi. And she is currently designing another one for L’Aquila, Italy, as a post-earthquake donation.

Rose calls Pepper’s work both ambitious and accessible. “How many artists have done these huge site-specific installations?” Rose asks. “You come up with Richard Serra or Michael Heizer. Often these works are aggressive, but Beverly is not hostile. She’s aiming at posterity. These materials are not going to go away. The fact that there’s a decision to make these outside works out of permanent materials that can’t be moved—that has to do with her ambition.”

David Collens , director of the Storm King Art Center in upstate New York, places Pepper’s work alongside sculptors like David Smith and Serra. “That show in Spoleto in 1962 was legendary,” he says. “Beverly may not be as recognized as other artists working on a large scale, but she has created her own aesthetic, and her individual works are as recognizable as a Serra or a Calder.”

Rose says Pepper would be better known had she lived in New York. “We used to kid about the fact that at the age of 90, she deserves the ‘Louise crown’: Nevelson and Bourgeois worked very hard, and finally in old age they got accolades. The question is, for Beverly, why didn’t she have that earlier? And I think it’s mainly because she stayed in Italy.” And yet her life abroad also nourished her aesthetic in profound ways. When she first moved to Italy, she discovered Renaissance art through the tutelage of her husband. But it was among Todi’s medieval architecture, its ancient Etruscan roots, that she found true inspiration. The city had a lasting influence on her work.

Pepper’s decision to settle in Italy was both personal and professional, but the salubrious Umbrian hills did not mean a quieter lifestyle. In four decades, everyone who is anyone in the worlds of Italo-American culture and diplomacy has made at least one, if not numerous, pilgrimages to the Todi castle of Signor e Signora Pepe. So many visitors returned to buy and restore their own castles and villas that the terrain around Todi earned the nickname Beverly’s Hills.

“ “When you walk this landscape it’s like being inside a spirit you can’t understand. It’s a kind of unexplainable dimension.” ”

——Beverly Pepper

American friends who followed the Peppers into the Todi real estate market include American art dealer Joseph Helman , former Yale president Benno C. Schmidt , the late actor Ben Gazzara and artist Al Held. Before he died, Time Warner Chairman Steven Ross bought a whole village. Younger friends have started making the pilgrimage as well. Film director Liz Garbus and her producer husband, Dan Cogan , had just visited with their two children this summer. In the late ’90s, the Peppers sold their castle (vertiginous steps became unmanageable as the years passed) to a pair of American multimillionaires, Peter Mullin and Miles Rubin , men with fortunes from finance and insurance, respectively.

The Peppers’ social set has always included bold-faced names from Hollywood, international art and politics. Pepper can riff about watching Supreme Court Justice Earl Warren’s boxer shorts drying on a line on a luxury yacht they shared (“They really should have paid to have their laundry done,” she says), and reminisce about Gellhorn dropping into their Rome house one day to beg Bill to go with her on an assignment to Africa, “because she didn’t know how to change tires.” Gellhorn continued working in international journalism after her marriage to Hemingway ended, often staying with the Peppers when she bounced through Italy. “Martha told me Hemingway was actually a coward,” Pepper says. “She said that during the war they had a flat in London, and when the bombers came overhead, he would drag her into bed to do whatever—he had to do that in order to escape his fear.”

AFTER DRESSING FOR A DINNER at Helman’s neighboring castle, Petacciolo, she gives a tour of the photo gallery on her bedroom wall, a veritable Life magazine montage of the postwar Italian-American scene. There’s Pepper in a white fur hat with Fellini; with Justice Warren on a yacht owned by the mother of The Washington Post publisher, Katharine Graham ; on the tarmac in front of a TWA flight just back from a jaunt to Angkor Wat with her 10-year-old daughter, the future Pulitzer Prize–winner Jorie Graham ; and in Rome, standing beside Norman Mailer. Among the dozens of famous faces gazing down at her when she sleeps are Ezra Pound , Mother Teresa, Hillary Clinton and American socialites Kitty Carlisle and Marietta Tree.

Looking at the pictures, she sighs. “I was told I had animal magnetism when I was young,” she says. “Now I regret that I didn’t use it more. I never had affairs to climb to the top, and I only regret one that I didn’t have, but that’s just because I actually liked him.”

She steps outside. Globes of green figs dangle from a tree near the kitchen door, silhouetted against the rising moon. In the distance, the ancient white stone circle of the town of Todi glows against fields of gold sunflower and green foliage, squares etched on the hills like patchwork.

“This is St. Francis country,” she says of Umbria. “What interests me is a spirituality that isn’t particularly religious. When you walk this landscape, it’s like being inside a spirit you can’t understand. It’s another dimension, a kind of unexplainable dimension. It’s like an aura outside my sculpture. I couldn’t work in New York City. Here, I feel like I have more space to fill. We live in a miracle here, even though we don’t all know it. The clouds. I never understood how the Greeks thought the gods lived in the sky, until I lived here, and then I saw it. Sometimes when I drive to the factory in Assisi, I look around and my heart just beats with it.”